The Bipolar Patients’ Family Experiences of the Outcomes of Encountering Stigma: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

Introduction: Nowadays, the most common psychological-social pressure to which bipolar patients’ families are exposed is stigma. Therefore, the present study was conducted to delve into the bipolar patients’ family experiences of the outcomes of encountering stigma.

Method: The study was of qualitative type. Purposive sampling was used to select the participants from the persons suffering from bipolar disorder and their families. Twenty seven of the participants were interviewed. The main data collection instrument was semi-structured interview with open questions. Additionally, the collected data were analyzed via inductive content analysis method. The accuracy and validity of the study rooted in four factors: credibility, transferability, verifiability, and reliability.

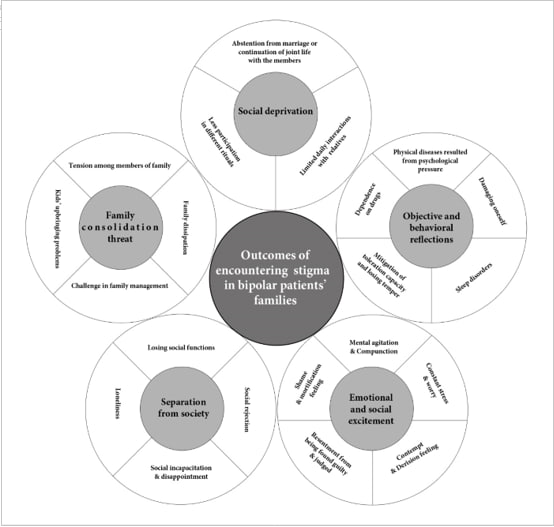

Results: Data analysis led to 1326 primary codes, which were further categorized into five main categories as the main outcomes of encountering stigma (social deprivation, emotional and sentimental excitement, objective and behavioral reflections, family solidarity threat, and separation from society) and 21 sub-categories.

Conclusion: Given then irreparable outcomes of stigma for bipolar patients’ family, it is necessary to take it into consideration. It is recommended to use media and also hygienic- treatment centers to educate different levels of society as to appropriate treatment with these patients and their families.

Key words: Stigma, Bipolar patient, Bipolar patients’ family, Qualitative content analysis

INTRODUCTION

Stigma is a Greek word mainly used to refer to body signals that imply the ethical abnormality of some people. Therefore, the concept of marked or blemished identity is not new, as humans have long had a natural tendency to categorize and isolate the different individuals (Goffman, 2003). Psychiatric patients are among these groups. In fact, stigma in patients suffering from psychiatric problems has been a common issue and is as old as human history (Bassirnia et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2016).

One of the most important, disabling, and severest psychiatric disorders is bipolar disorder that is common in one percent of the people in society. Having the risk of death, it is recognized as the seventh cause of distress in the world. The rate of suicide in these patients fluctuates from 15 to 20%. Bipolar disorders in DSM-5 is typically depicted as a group of brain disorders that brings about severe fluctuation in temperament, energy, and performance of people. It is usually categorized among depression and schizophrenia disorders (Gonzalez et al., 2007; Kaltenboeck, Winkler, & Kasper, 2016; Maji, Sood, Sagar, & Khandelwal, 2012; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Due to factors such as inappropriate conditions and costly care of psychiatric patients in health care centers, low level of cooperation of supportive and insurance organizations, and also the policy of deinstitutionalization movement, the responsibility of caring these patients is mainly on the shoulder of families. More than 60% of these patients return to their families after being discharged from health care centers. Given this, family is the first and most important source of caring them (BİLİR, 2018; Kahanipour, Zare, Shams, & Borjali, 2011; Miklowitz, Goldstein, Nuechterlein, Snyder, & Mintz, 1988). The experience of caring bipolar patients can be different from that of other psychological patients as it has a different nature. In fact, this disorder has a periodic and fluctuated status, which, in turn, makes it difficult to predict the conditions of patient for families (Bruni et al., 2018; Reinares et al., 2006).

Stigma refers to a set of negative attitudes and perspectives toward a specific state that affects both the person and family. This kind of stigma is called contagious or communicative stigma. The outcomes of these diseases for the patients and their families are more than the disease itself (Dubey, Arivazhagan, Sharma, Sreeraj, & Uvais, 2020; Goffman, 2003; Ocisková et al., 2014). The common outcomes of these diseases for families include loneliness, disrespect, discrimination, and indifference feelings, which lead to behaviors including hiding the diseases, delay in treatment, and avoiding other people (Baruch, Pistrang, & Barker, 2018; Gutiérrez-Rojas, Jurado, & Gurpegui, 2011). Wait and fear of being dispelled cause the patients and their families to have low confidence and deprive themselves from social relations. Because of this, weakening of life conditions, reduction of income, and unemployment would be likely to be seen in their families (Ogilvie, Morant, & Goodwin, 2005; Pompili et al., 2014; Robbins, Monahan, & Silver, 2019).

The concept of stigma, as a psychiatric disease, is rooted in culture and different societies have different interpretations of it. To put it more clearly, in collective cultures, which are mostly in Asian countries, including Iran, there are more stigmatizing attitudes regarding psychiatric patients in that these societies emphasize collective and self-concept norms. Because of this, stigma phenomenon is more tangible in these countries (Alem & Kebede, 2003; Mohamadi, Mohtashami, & Arabkhangholi, 2017). What is understood from the previously conducted studies is that people of most countries do not take a positive attitude toward psychiatric patients and their families. Further, the fear of being stigmatized is the main and most important hurdle of the patients and their families to use social supports and treatment services; and that is why 40% of the families hide the hospitalization of their patients from others (Kaushik & Bhatia, 2013; Vasudeva, Sekhar, & Rao, 2013; Zhang et al., 2019).

Although stigma has been recognized as a global phenomenon, the experience of bipolar patients’ families and the discriminations to this disease is different across countries and even cities. In developed countries, compared with less developed ones, more studies have been undertaken on the concept and dimensions of stigma in various psychiatric disorders, developing tools to measure it, and proposing interventions to mitigate this phenomenon. The point, however, is that a considerable percentage of these patients exists in less developed countries (Aziz, Akhtar, & Hasan, 1997; Becker & Arnold, 1986). Iran is among developing countries that has a high statistics of bipolar disorder and stigma. Despite this high rate, few studies have been conducted in this regard in Iran (Mohammadi, Mohtashami, & Arabkhangholi, 2017; Seguin, 1976).

Given the high statistics of this disease, limited studies on stigma in the families of bipolar patients, ever-increasing outcomes of social stigmatization to this vulnerable group, and culture-dependent nature of stigma, this study aimed to look into this concept deeply by exploring the experience of bipolar patients’ families of the outcomes encountering stigma.

Methods

Study design

The present study was of qualitative type and used inductive content analysis method to examine the experience of bipolar patients’ families of the outcomes encountering stigma. The study is exploratory in terms of purpose and applied in terms of results. The study was conducted at Razi psychiatric hospital in Tehran city. Having 1375 beds, this hospital is the biggest and oldest psychiatric hospital in the country.

Participants

The main participants of the study, which were selected via targeted sampling method, were bipolar patients’ families who referred to the hospital for hospitalizing their patients in the first half of 2021.

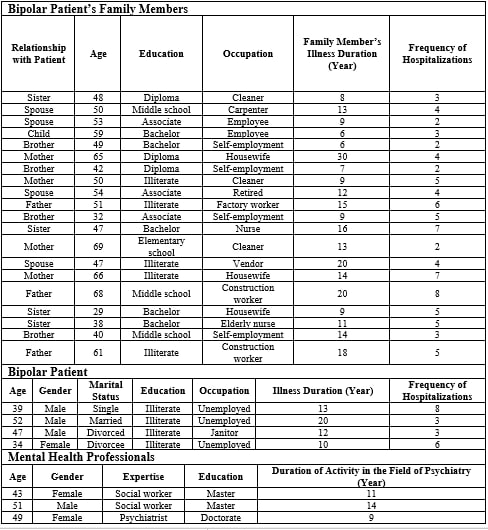

The main criteria to enter the study were being the main member of family, having the experience of living with the patient in one house for at least two successive years, passing at least two years from the beginning of the patients’ symptoms, ability to communicate, and informed participation. In total, 20 members of the bipolar patients’ families, four bipolar patients, and three psychiatric experts took part in the study; and data saturation was achieved by interviewing 27 persons. Specifications of participants in research are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of research participants

Data collection

The process of data collection was done in spring and summer of 2021. The main method of data collection was relatively deep semi-structured (face-to-face) interviews with open questions. Therefore, given the conditions of the participants and type of their information, it was possible to modify questions. The interviews started with a general question and continued with the most relevant questions. Probing questions (such as “would you please elaborate on this case?”) were also used so that the participants could completely explain their experiences and add to the enrichment of data. Additionally, descriptive notes and field notes were also used to monitor the interviews more skillfully. Finally, each interview lasted from 30 to 90 minutes.

Data analysis

The participants’ permission was obtained to record the interviews. All the interviews were listened several times and were then transcripted manually, compared with the recorded interview, and finally typed in Microsoft office. Data analysis was fulfilled during data collection process. In other words, every interview was analyzed and then another interview was done. Graneheim & Lundman approach (Graneheim, Lindgren, & Lundman, 2017) was utilized for the analysis of data. To put it more specifically, after checking the written interviews line by line, key points were determined and coded to specify primary codes. Then, similar codes were given a joint title. The joint and similar codes were then merged to form main categories and also sub-categories. The coding and categories were double checked by researcher colleagues and the final coding and categorization was done after comparing and modifying them with the pertinent literature. It took eight months to do the sampling and aanalysis procedures (April to November of 2021). Finally, MAXQDA 2020 was used in the coding process of data.

Rigor of the study

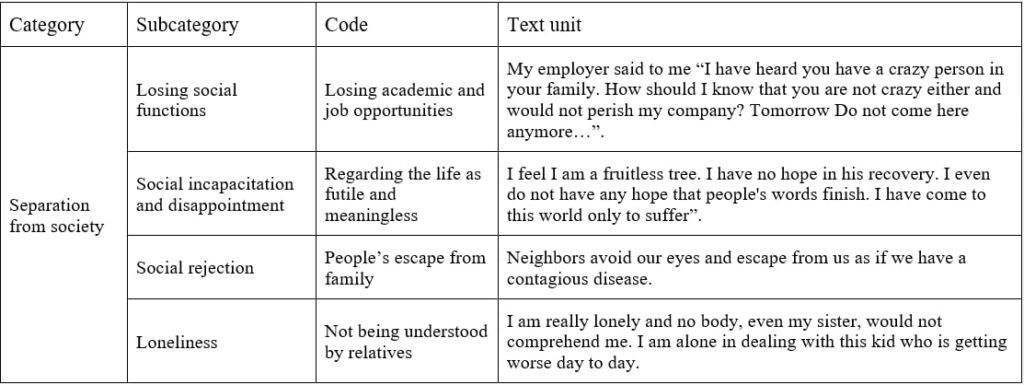

The criteria offered by Guba and Lincoln (1985) were used for the credibility and trustworthiness of data (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). To put it another way, over the analysis process, the study findings were discussed with supervisor professors as well as professors who were familiar with qualitative research. In addition, external supervisors were required to delve into the extraction of codes, sub-categories, and parts of the interviews. During the study, the researchers tried to be engaged with the participants for a long time, attend the research field for a long time (eight months), and use effective data collection tools. It was also tried to provide precise explanations regarding the study, especially the under-study population so that other researchers would be able to replicate the study. In order for the verifiability, it was also attempted to avoid any pre-judgement, omit some of unexpected data, and regard integrity in all stages of the study. Finally, for more confidence, all the codes and topics were checked in a Focused Group Discussion (FGD) with three psychiatric experts to confirm their correctness. Table 2 gives an example of the process of coding and class formation.

Table2: An example of a coding process (Separation from society formation)

Ethical considerations

Prior to the commencement of the study, the oral and written consent of the participants to take part in the study and record their voice were obtained. They were also assured as the confidentiality of their names. They were explained that they can freely continue or leave the interview at any time. Furthermore, the researchers did their best to avoid any terms and labels that might upset the participants; and also avoid any prejudgment and bias to regard the scientific and ethical requirements of research.

RESULTS

This study was accomplished with the purpose of examining the experiences of bipolar patients’ families regarding the outcomes of encountering stigma. To this end, 27 participants took part in the study from whom 20 ones were members of these patients’ families (25% spouse, 15% father, 20% mother, 20% sister, and 20% brother). The mean and SD of age (50/9±11/41), time of the diseases (12/95±5/87), and number of hospitalization of patient (4/3±1/7) were also calculated for them. Four bipolar patients also took part in the study (25% female and 75% male). They were all illiterate, 25% of them were married, 25% single, 25% divorced, and 25% abandoned. The mean and SD of age (43±8/04), time of disease (13/75±4/34), and number of hospitalization (2±5/49) were also estimated for them. Three psychiatric expert also attended the study, which included two master and one doctorate social case workers. The mean and SD of age and activity in psychiatry were also calculated for them (66±3/39 and 11/33±2/05, respectively).

Data analysis led to 1326 primary codes, which were categorized into five main categories as the main outcomes of encountering stigma (social deprivation, emotional and sentimental excitement, objective and behavioral reflections, family solidarity threat, and separation from society) and 21 sub-categories. In Figure 1, subcategories, categories and themes are shown

Figure 1. Introducing subcategories, categories, and themes of the research

Social Deprivation

Abstention from marriage or continuation of joint life with members of patient’s family was one of the outcomes that was referred to by eight participants. A 59-year old child of the patient said: “one of my brothers has a doctorate degree of economy and is a good boy in every term. However, whenever he has gone to propose to a girl, he has been rejected as soon as they understand that our mother is sick. Why my brother should not have a good marriage with his desirable conditions?”.

Limited daily interactions with relatives was also a common outcome referred to by 16 participants. Seventeen-year old sister of a patient said: “when my friends understood about the story, they started to deride me. I cut my relationship with them and do not respond their calls because I feel worse being with them”.

Less participation in different rituals was another outcome mentioned by seven participants. 29-year-old sister of a patient said: “before my brother’s disease, we always had Imam Hussein’s bereavement and other religious ceremonies. After that, we cancelled all of them. Now, even our relatives would not invite us to their children’s wedding parties”.

Emotional and Sentimental Excitement

Mental agitation and compunction were among the outcomes that were often mentioned by patients’ parents. A 51-year-old father said: “I am agitated day and night. I cursed myself a lot. Sometimes, I said to myself maybe people are right and my gene had a problem that caused me to have such a kid; or maybe, as others say, I have not taken care of him adequately. I keep damning myself”.

Constant stress and worries was also another outcome highlighted by 13 participants. Spouse (53 years old) of one of the patients said: “ stress and anxiety is always with me and even when everything is good, I still feel stress that something bad is going to happen. Sometimes I have severe headache, heartbeat, and nausea”.

Seven participants also referred to resentment from being found guilty and judged. A 69-yer-old mother said:” everybody thinks that because we do not take care of him or hit him at home, he has this problem. They also think that we had an elf at home and gave it to this child. To make a long story short, all think that it is our fault and it really bothers us”.

Furthermore, 15 participants also referred to contempt and derision feeling as an outcome of the disease. A 42-years-old brother said: “can you believe that even your wife derides you and tells you that you had better go to your crazy sister. When your wife behaves like that, what can I expect from others? Wherever we go, people look at us with derision and talk with us as if we are foolish and crazy”.

Shame and mortification feeling was also mentioned by 11 participants as the outcome of the disease. A father who was 61 years old stated “we are graceful people and saving our face is the most important thing for us. Since we have stepped into hospital for our son; and our neighbors found about the story of our son, they somehow gibe us. We really feel ashamed”.

Objective and Behavioral Reflections

Mitigation of toleration capacity and losing temper was another outcome that seven participants pointed out. A 40-year-old brother said: “ I easily lose my temper while dealing with people. When they act in a way that annoys me, I start to curse them. I was not so impatient in the past”.

Sleep disorders was another outcome that 14 participants highlighted in their interviews. A 60-year-old father stated: “my wife and I take shifts in turn and try to take care of ourselves that nobody suddenly kill us with a knife. Even if we lie down to rest, we cannot sleep as we cannot stop thinking about people’s taunts and ironies. We can sleep only with help of tablet”.

Three participants pointed to damaging oneself as the outcome of the disease. A mother aged 65 years old remarked “when I saw that even my own sister mocked use, I really backed off and took all the tablets in the cupboard to get rid of this life; but I was taken to hospital and I survived”.

Dependence on drugs was mentioned by six participants. A brother aged 42 years old said “ when I go home I feel fray and cannot relax until I smoke some cigarettes. When smoking cannot help me to relax, I take opium to get rid of thinking about this damn life”.

Appearance of physical diseases from mental pressure was another outcome that was referred to by seven participants. A sister aged 47 years old stated “I got psoriasis because of my mental pressures. It is a dermal disorder. I am always under care. Doctors say it is a mental disease”.

Family Consolidation Threat

Challenge in family management was the other outcome that three participants pointed out. A sister with 47 years age said “our life is not certain. I can decide for neither my children nor myself. I cannot control any of them. I have recently been given a twin by God. However, I cannot find time to take care of them”.

Another outcome was tension in family management that was mentioned by nine participants. A 68-year-old father remarked “there is always fight in our house. Just last night my oldest son was disputing that why we do not take him to welfare clinic so that all would relax. His mother said with sadness that he is my child and I cannot do that. We always have these kinds of disputes at home”.

Two participants also referred to family dissipation. A 66-year-old mother said “since my child got sick and was hospitalized, our family destroyed. My husband abandoned us and remarried. My children also went to think something about their own life. One of my sons became addicted and wandered and nobody has any news of him”.

Three ones also pointed to upbringing-related problems of children. A spouse aged 54 years old stated “I did not know whether I should take care of my sick husband, respond to people’s words, or bring up my children. My children are now all impolite and I cannot control them anymore. My son has become so stubborn and my daughter does not listen to me at all and does not come home until late at night. There was nobody to teach them how to live correctly”.

Separation from Family

Social rejection was one of the outcomes that ten participants mentioned in their interviews. A 32-year-old brother stated “well, the people in our neighborhood are afraid of us. They fear that we may cause problems for them. That is why, they try to avoid us and when they see us, they behave as if they have seen something dreadful”.

Social incapacitation and disappointment was also mentioned by seven interviewees. A mother aged 66 years old stated “others’ behavior causes me to become hopeless of life. I say to myself that if other mothers work hard for their children, they will see its results. But, what about me? Well, when you have a tree that does not bear, do not you get upset? To make it worse, when there is no hope about his treatment and future, one would feel absurd and futile”.

Nine participants also referred to loneliness. A father aged 68 years old said “ I have no relationship with any person. I do not know how to describe my feeling. I am very lonely. Very very lonely… Nobody comprehends me… I feel awful and there is nobody that understands me”.

Finally, eight ones referred to losing social functions. A spouse who was 47 years old satated that “my nine years old daughter says that every person in her school mocks her. She does not like to study. She is thinking about leaving school. In the morning, she pretends to be asleep for not going to school. I send her to school with coercion and cry. I am a construction worker. My job conditions could have been much better than this. However, because all call us “the family of crazy people”, I cannot find a job in a company”.

DISCUSSION

The thrust of this study was to explore the experience of bipolar patients’ families regarding the outcomes of encountering stigma. According to the obtained results, social deprivation is one of the most important outcomes for the families, which, in turn, results to less participation in different rituals, limited daily interactions with relatives, and abstention from marriage or continuation of joint life with the members of patients’ family. These results are in accordance with those of Reinares(Reinares et al., 2006), Vasudeva (Vasudeva et al., 2013), and Baruch (Baruch et al., 2018), as they have also reported examples of social deprivation following stigma experience, including marriage-related problems and limited interactions with relatives.

According to the study results, objective and behavioral reflections, such as mitigation of toleration capacity and losing temper, sleep disorders, damaging oneself, dependence on drugs, and physical diseases emanated from mental pressure, are among the outcomes of encountering stigma for the families, which comply with those of Ogilvie (Ogilvie et al., 2005) and Robbins (Robbins et al., 2019). Stigma-related psychological tensions and pressures cause many of the members of these families to act violently, take drugs, or damage themselves in order to reduce or counter these tensions.

Another outcome of stigma for the families is emotional and sentimental excitements that might appear in society in varying forms, such as mental agitation and compunction, constant stress and worries, resentment from being found guilty and being judged, contempt and derision feeling by others, and shame and mortification feelings. These findings are in line with those of Pompili (Pompili et al., 2014) and Maji (Maji et al., 2012).

Furthermore, another outcome of stigma for these families was family consolidation threat that included challenge in family management, tension among members of family, family dissipation, and upbringing-pertinent problems of children. These findings accord with those of Miklowitz (Miklowitz et al., 1988), Kaushik (Kaushik & Bhatia, 2013), and Zhang (Zhang et al., 2019), in that they have also highlighted the risk of family dissipation because of experiencing psychological diseases stigma.

One of the most important impacts of stigma for the families was separation from society, which, in turn, included social rejection, social incapacitation and disappointment, and losing social functions. This finding was in line with that of Gutiérrez-Rojas (Gutiérrez-Rojas et al., 2011) and Zhou (Zhou et al., 2016). According to the responses of many of the participants, social isolation and taking distance from society, which are followed by disappointment and loneliness, are among the most common outcomes of stigma for bipolar patients’ families.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicated that in Iran, stigma experience and stigmatization by the society has numerous outcomes for the bipolar patients’ families. The range of these outcomes is very wide ranging from resentment from relatives and slight worries to separation from society and even suicide. The effect of this phenomenon on the family members is related to not only toleration, self-confidence, and individual features; but also cultural-social factors, traditions, beliefs, attitudes, and awareness of the society, especially the relatives of the patient’s family.

Thus, in order to reduce the effects of stigma on these families, it is necessary to pay special attention to these families and ask help from psychological experts to give technical interventions to enhance their individual skills, including self-confidence and toleration. Also, macro-level planning and policy making through public media should be taken into consideration to raise the awareness of society regarding this disorder and normalize it in the society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The present study is part of a Ph.D. dissertation (ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.249) in social work approved by the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences. We would like to appreciate the full cooperation of the university officials, the staff of Razi Psychiatric Hospital, as well as the patients and their families who participated in this study.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Alem, A., & Kebede, D. (2003). Conducting psychiatric research in the developing world: challenges and rewards. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(3), 185-187.

Aziz, H., Akhtar, S. W., & Hasan, K. Z. (1997). Epilepsy in pakistan: Stigma and psychosocial problems. A population‐based epidemiologic study. Epilepsia, 38(10), 1069-1073.

Baruch, E., Pistrang, N., & Barker, C. (2018). ‘Between a rock and a hard place’: family members’ experiences of supporting a relative with bipolar disorder. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 53(10), 1123-1131.

Bassirnia, A., Briggs, J., Kopeykina, I., Mednick, A., Yaseen, Z., & Galynker, I. (2015). Relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their treatment partners. Psychiatry research, 230(2), 436-440.

Becker, G., & Arnold, R. (1986). Stigma as a social and cultural construct. In The dilemma of difference (pp. 39-57): Springer.

BİLİR, M. K. (2018). Deinstitutionalization in Mental Health Policy: from Institutional-Based to Community-Based Mental Healthcare Services. Hacettepe Sağlık İdaresi Dergisi, 21(3), 563-576.

Bruni, A., Carbone, E. A., Pugliese, V., Aloi, M., Calabrò, G., Cerminara, G., . . . De Fazio, P. (2018). Childhood adversities are different in schizophrenic spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. BMC psychiatry, 18(1), 391.

Dubey, I., Arivazhagan, K., Sharma, S., Sreeraj, V., & Uvais, N. (2020). Perceived Stigma Towards Psychiatric Illnesses in Mental Health Trainees: A Cross-Sectional Study.

Goffman, E. (2003). Stigma. Praha: Sociologické nakladatelství (SLON).

Gonzalez, J. M., Perlick, D. A., Miklowitz, D. J., Kaczynski, R., Hernandez, M., Rosenheck, R. A., . . . Bowden, C. L. (2007). Factors associated with stigma among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder in the STEP-BD study. Psychiatric services, 58(1), 41-48.

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse education today, 56, 29-34.

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of qualitative research, 2(163-194), 105.

Gutiérrez-Rojas, L., Jurado, D., & Gurpegui, M. (2011). Factors associated with work, social life and family life disability in bipolar disorder patients. Psychiatry research, 186(2-3), 254-260.

Kahanipour, Zare, Shams, & Borjali. (2011). Relationship between shame-focused attitudes toward mental illness and levels of emotion expressed in relatives of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Annual Conference of the Scientific Association of Psychiatrists of Iran, 28.

Kaltenboeck, A., Winkler, D., & Kasper, S. (2016). Bipolar and related disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-10. CNS spectrums, 21(4), 318-323.

Kaushik, P., & Bhatia, M. (2013). Burden and Quality of Life in Spouses of Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder.

Maji, K., Sood, M., Sagar, R., & Khandelwal, S. K. (2012). A follow-up study of family burden in patients with bipolar affective disorder. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(2), 217-223.

Miklowitz, D. J., Goldstein, M. J., Nuechterlein, K. H., Snyder, K. S., & Mintz, J. (1988). Family factors and the course of bipolar affective disorder. Archives of general psychiatry, 45(3), 225-231.

Mohamadi, Mohtashami, & Arabkhangholi. (2017). Stigma towards patients with mental disorders. Iranian journal of Systematic Review in Medical Sciences

1(1), 61-72.

Mohammadi, Mohtashami, & Arabkhangholi. (2017). Stigma is more common in patients with mental disorders. Systematic Review of Medicine in Medical Sciences, 1(1), 61-72.

Ocisková, M., Praško, J., Kamarádová, D., Látalová, K., Kurfürst, P., Dostálová, L., & Ticháčková, A. (2014). Self-stigma in psychiatric patients–standardization of the ISMI scale. Neuroendocrinology Letters, 35(7), 624-632.

Ogilvie, A. D., Morant, N., & Goodwin, G. M. (2005). The burden on informal caregivers of people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar disorders, 7, 25-32.

Pompili, M., Harnic, D., Gonda, X., Forte, A., Dominici, G., Innamorati, M., . . . Janiri, L. (2014). Impact of living with bipolar patients: Making sense of caregivers’ burden. World Journal of Psychiatry, 4(1), 1.

Reinares, M., Vieta, E., Colom, F., Martinez-Aran, A., Torrent, C., Comes, M., . . . Sánchez-Moreno, J. (2006). What really matters to bipolar patients’ caregivers: sources of family burden. Journal of affective Disorders, 94(1-3), 157-163.

Robbins, P. C., Monahan, J., & Silver, E. (2019). Mental Disorder, Violence, and Gender. In Clinical Forensic Psychology and Law (pp. 157-168): Routledge.

Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. (2003). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. IV (4th.

Seguin, C. A. (1976). Folklore psychiatry: A neglected aspect of psychiatric studies. Transnational Mental Health Research Newsletter.

Vasudeva, S., Sekhar, C. K., & Rao, P. G. (2013). Caregivers burden of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a sectional study. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 35(4), 352-357.

Zhang, X., Zhao, M., Li, J., Shi, L., Xu, X., Dai, Q., . . . Zhang, X. (2019). Associations between family cohesion, adaptability, and functioning of patients with bipolar disorder with clinical syndromes in Hebei, China.

Journal of International Medical Research, 47(12), 6004-6015.

Zhou, Y., Rosenheck, R., Mohamed, S., Ou, Y., Ning, Y., & He, H. (2016). Comparison of burden among family members of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in a large acute psychiatric hospital in China. BMC psychiatry, 16(1), 1-10.

Table 1: Characteristics of research participants

Table2: An example of a coding process (Separation from society formation)

Figure 1. Introducing subcategories, categories, and themes of the research