Stigma in patients with bipolar disorders and their families: A systematic review

Dr.Maryam Latifiyan ,Dr. Ghoncheh raheb

Abstract

Introduction: Stigma affects different life aspects in patients with bipolar disorder and their families. However, stigma and its consequences on such patients are rarely studied. Therefore, this study aimed to review stigma in patients with bipolar disorder and their families.

Methods: We conducted a systematic review using five online databases (“PubMed”, “Scopus”,”Medline”, “Embase” and “Web of Science” databases). Articles published in the English language about stigma in bipolar patients and their families from 2011 to October 2021 were included. PRISMA method was used to analyze the data.Results: A total of 785 articles were retrieved, of which 33 articles from 14 countries were selected and included in the study (n=6206 subjects). Of the 33 articles, 25 adopted quantitative methods (75.75%), two used combined (6.06%), five used qualitative (15.15%) methods, and one was a case series (3.03%). The results of the studies were categorized into four groups: stigma in family members and caregivers of the

patients, predictors, consequences, and strategies for coping with stigma in such patients and their families.

Conclusion: Our results showed that stigma was experienced by a significant percentage of patients with bipolar disorder and their families. Stigma affected different aspects of their lives. Given the impact of stigma on the quality of life in such patients and their families, further studies are needed to reduce stigma in this group.

Keywords: Stigma, Internal Stigma, Bipolar Disorder, Bipolar Patient Family, Systematic Review

Introduction Psychiatric disorders are one of the five leading causes of disability. Bipolar disorder is one of the most persistent, important, and severe psychiatric disorders. According to global statistics, it occurs in approximately 1% of the population and is equally common in both genders (Jolfaei et al., 2019, Angst, 2013). Bipolar disorder is described in the DSM-5 as a group of brain disorders that cause extreme fluctuation in mood, energy, and function, ranging from depressive to schizophrenia. People with bipolar disorder experience periods of excitement, overactivity, delirium, and euphoria (known as mania), and other periods of feeling sadness and hopelessness (known as depression) (Kaltenboeck et al., 2016)

Today, due to undesired conditions and costly care of patients with psychiatric disorders in medical centers, poor cooperation between supportive organizations and insurance companies, and de-institutionalization movement policies, only families are responsible for caring for such patients (BİLİR, 2018, Ghai et al., 2013). The experience of caring for such patients can be different from other mental illnesses. The reason for this difference goes back to the nature of the disease. Because it has a periodic state and has an oscillating nature (Bruni et al., 2018). Stigma is one of the most common and challenging social issues that affect patients with bipolar disorder (Sharma et al., 2017, Grover et al., 2019). Stigma can be considered a combination of three problems: lack of knowledge (ignorance and misinformation), negative attitudes (prejudice), and rejection or avoidance behaviors (discrimination) (Goffman, 2003, Henderson et al., 2013). The history of stigma and rejection from society backs to ancient times (Gur et al., 2012). The presence of stigma is the most serious concern for patients; because they have to cope with the disease’s problems and symptoms and have to adapt to negative attitudes and society labeling (Sibitz et al., 2011, Wong et al., 2009, Knight et al., 2006). Stigma impairs patients’ quality of life and leads to their isolation and rejection of interpersonal relationships. Patients’ rejection from society and low self-esteem, following the fear of rejection, weakens living conditions, reduces income, and causes unemployment (Connell et al., 2014).

Stigma is also common among families of patients with bipolar disorder. The parents of such patients, reprimanding by ordinary and professional people, look for the causes of the disease and experience issues such as guilt attribution and social exclusion due to having a family member with such disorder (McCann et al., 2011, Koschorke et al., 2014). Family stigma contributes to decreased self-esteem, sleep disorders, decreased psychological well-being, and reduced quality of life (Wong et al., 2009). Another consequence of stigma is the inability of families to seek treatment. About 50%-60% of patients with neurological problems refuse treatment or care for such patients due to fear of stigma (Park and Park, 2014). In the study by Endo et al., one of the reasons for the delay in counseling was concerned about people’s thoughts (Ando et al., 2013). In addition, stigma increases the risk of suicide and is cited as one of its causes. Stigma is also one of the main reasons for increased recurrence (Aggarwal et al., 2014). Although stigma is a global phenomenon, the experience of dealing with it and the discrimination varies across countries and even cities. In general, the reaction of people in the community to patients with psychiatric disorders can vary depending on the severity of illness, culture, and changes over time (Keshavarz et al., 2018, Shamsaiee et al., 2013). There are limited studies on stigma in such patients and their families. Therefore, the present study aimed at evaluating the predictors, consequences, and strategies to combat stigma in patients with bipolar disorder and their families.

Methods

This was a secondary study conducted as a systematic review, and its main goal was to analyze research findings on stigma in bipolar patients and their families and to achieve new results by pooling the results of previous research in a quantitative framework. In this research, studies were initially categorized based on the subject under study, and then the methods employed were reviewed. In this study, the Prisma method was used to analyze the data. The inclusion criteria were: articles published in English between 2011 and 2021, presence of stigma in patients with bipolar disorder or their families, and complete and accurate reporting findings and research methods. Exclusion criteria comprised the unavailability of full text, being a review study, and the lack of a clear explanation of research methods. Considering the statistical population of the research, the data obtained from the studies were categorized in terms of the subject, methodology, and validity and then analyzed. Before conducting the literature review, a form was prepared according to study goals and presented to the research team for data extraction after teaching them how to complete it.

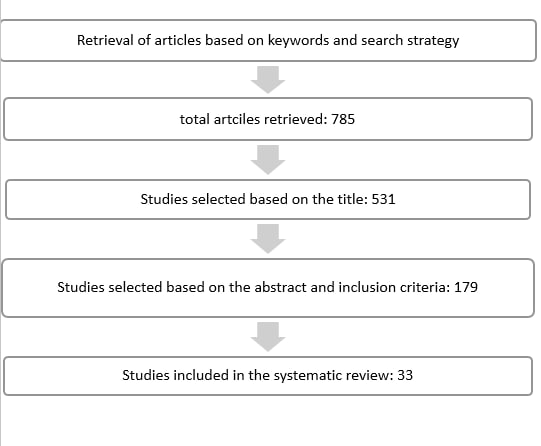

The statistical population of this study included all the English articles conducted as descriptive, survey, correlation, case report, cohort, experimental, quasi-experimental, qualitative, and mixed-method studies on stigma in bipolar patients and their families between 2011 and 2021. For this purpose, the keywords of “bipolar disorder”, “manic”, “depression”, “hypomania”, “cyclothymic”, “stigma”, “self-stigma”, “discrimination”, “public stigma”, “internalized stigma “,” mental illness stigma “,” attitudes towards mental illness “,” stigmatization “,” bipolar patient family”, and ” caregiver of the bipolar patient ” were searched in the “PubMed”, “Scopus”, “Medline”, “Embase “, and “Web of Science” databases. In the first stage, a total of 785 articles were identified. In the second step, the titles of the articles that were probably related to the topic of the present study were reviewed. After assessing the articles in terms of design and quality criteria by four experts in the fields of social work, psychology, and rehabilitation, 531 articles that met the least scientific requirements for being included in a systematic review were chosen. In the third step, after reviewing the abstracts of articles, several articles unqualified for being included in the study were omitted, leaving 179 articles. Then in the fourth step, the abstract was read carefully, and methodology was analyzed to provide an accurate definition and explanation of the target group, study design, sampling method, sample size, and the validity and reliability of data collection tools. Finally, 33 articles remained for final evaluation. Figure 1 shows the process of the inclusion and exclusion of primary studies until reaching the final synthesis.

To increase the validity of findings, three researchers independently performed a literature search in different databases, initial assessment of articles, qualifying articles, and checking their compliance with inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the case of disagreement, the consensus was reached with the help of a fourth researcher. In this study, the researchers observed ethical considerations in all steps and were required to collect the data honestly, accurately, and completely.

Figure 1. The process of the inclusion and exclusion of articles in the present research

Results

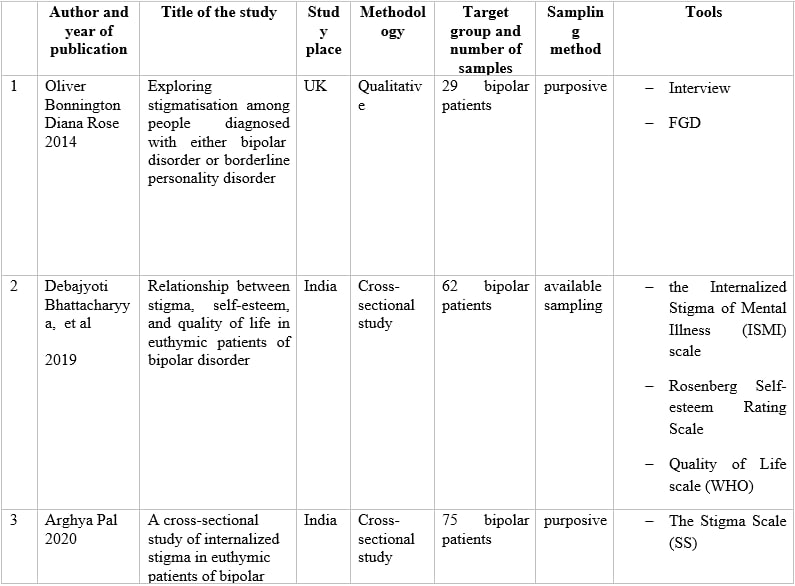

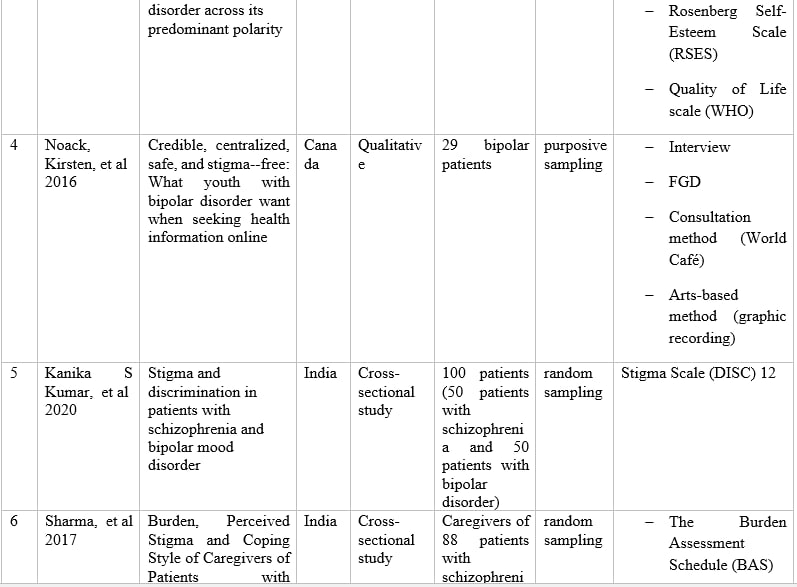

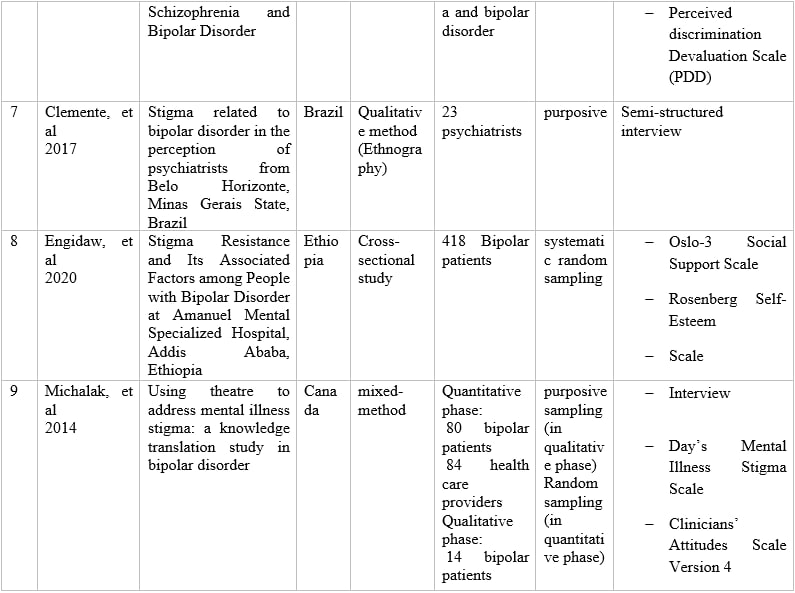

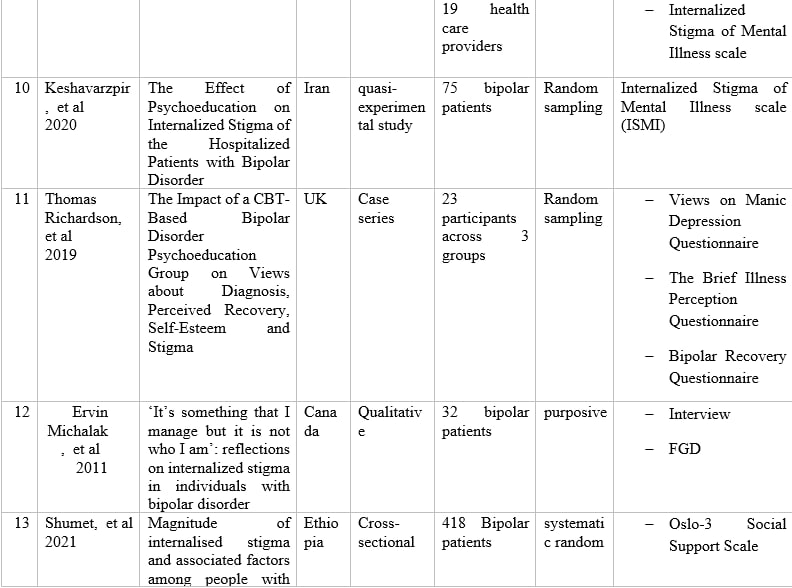

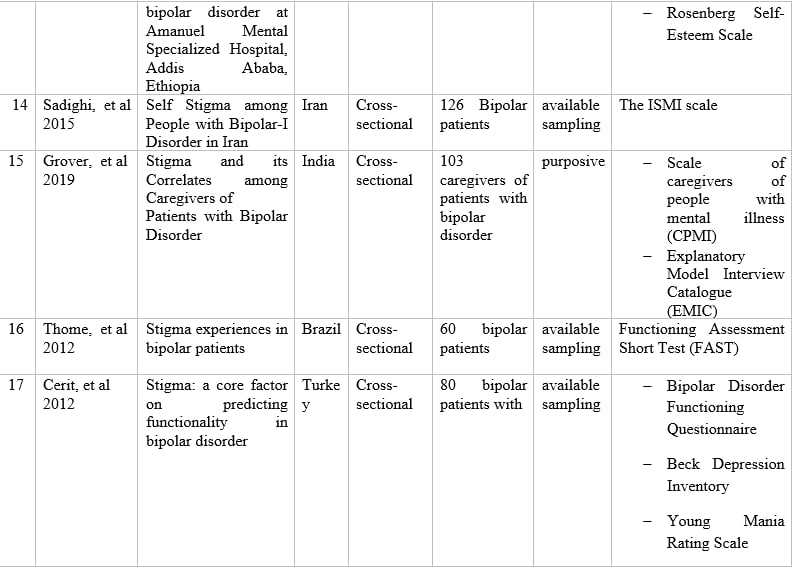

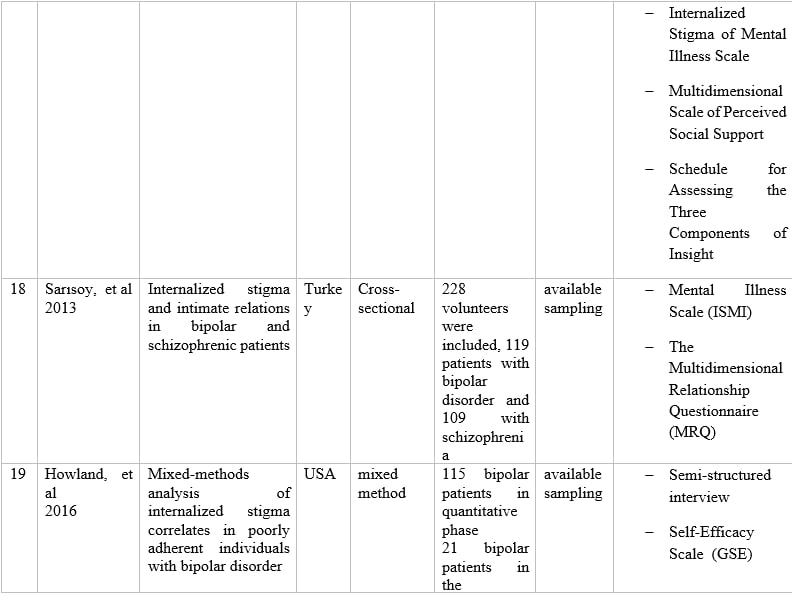

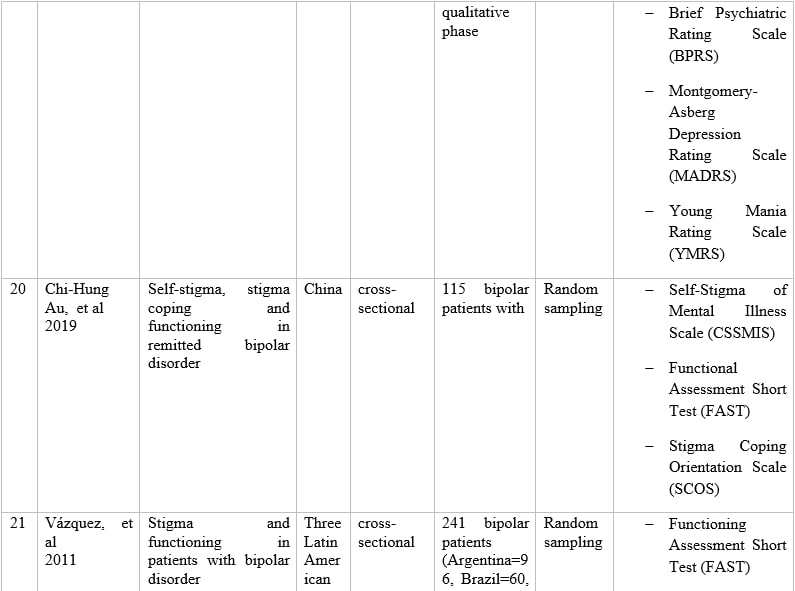

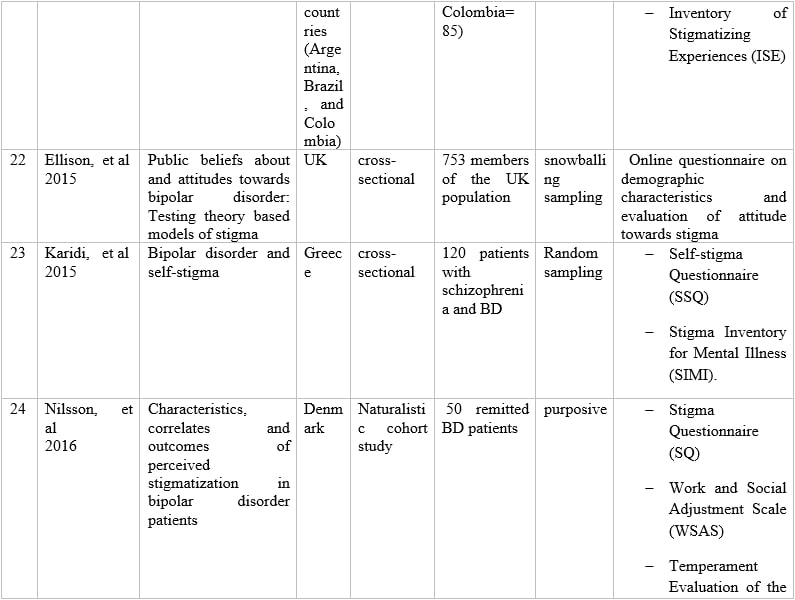

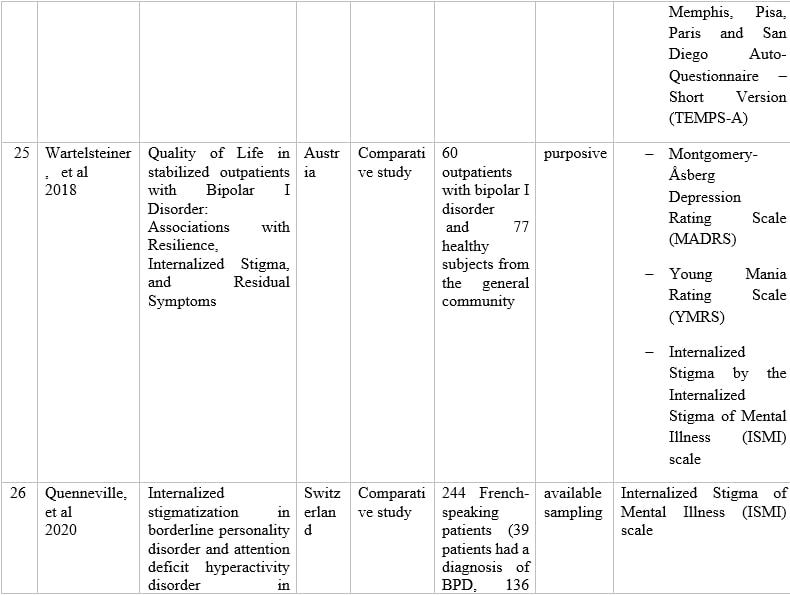

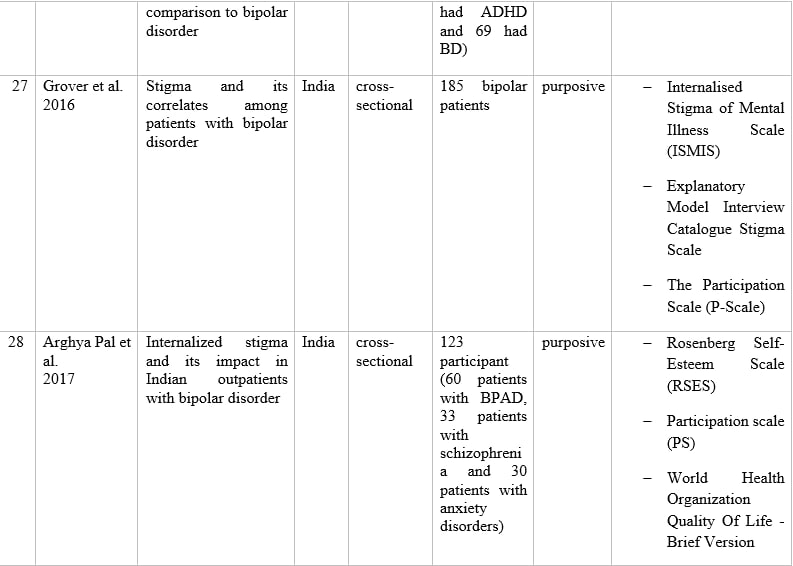

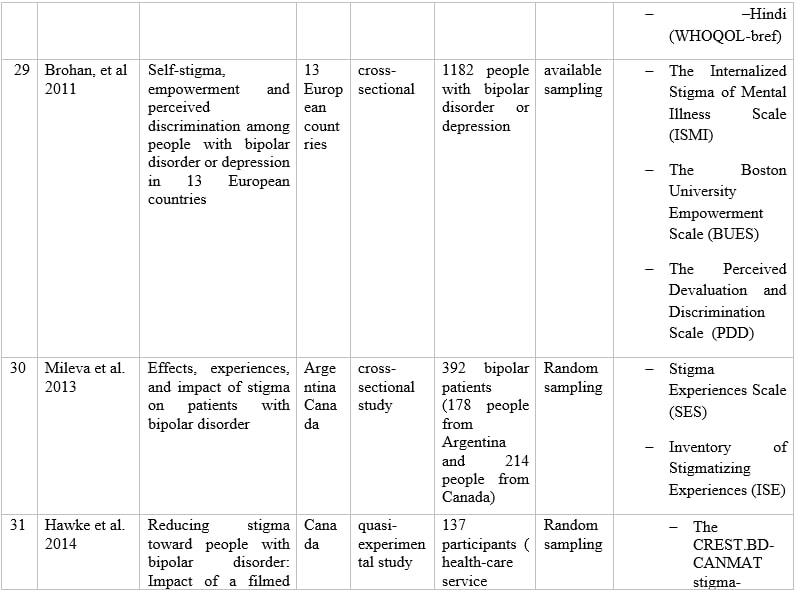

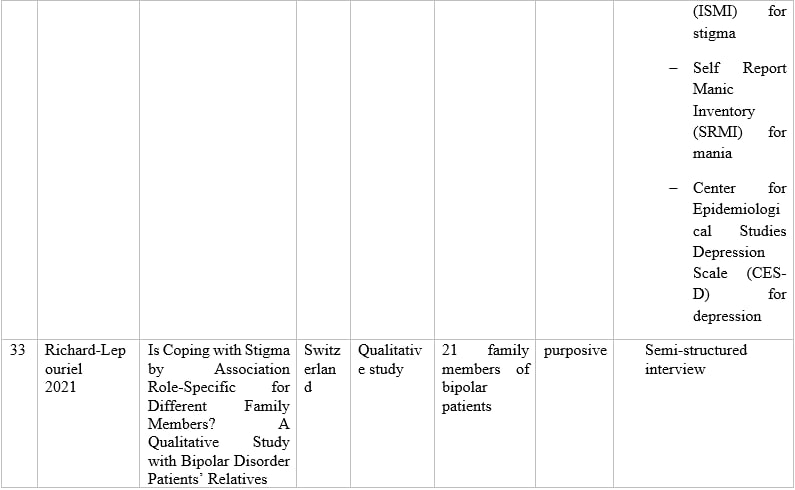

Table 1 – Information of articles that met the inclusion criteria.

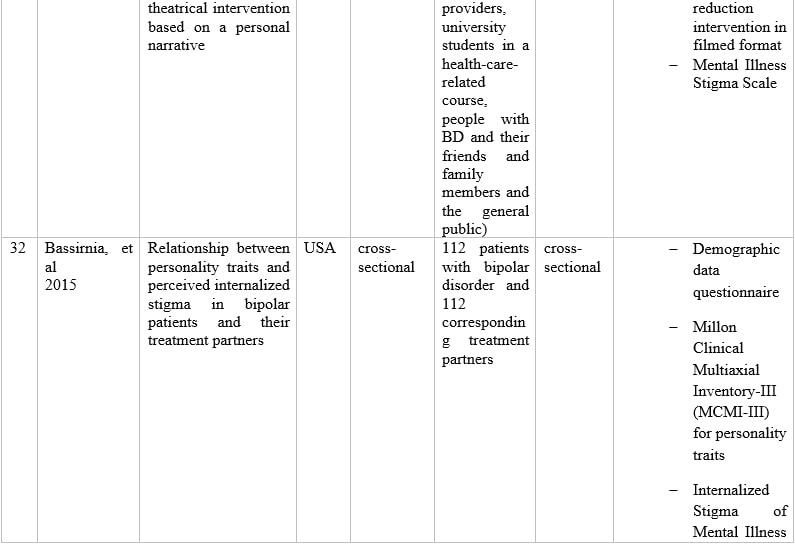

After searching and qualitative evaluation of the studies during a systematic review, in the end, the final synthesis was performed on 33 articles. As it turns out in table 2, quantitative research has accounted for a larger share of studies.

Table No. 2 – Frequency distribution of articles by research method

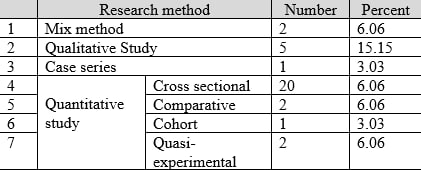

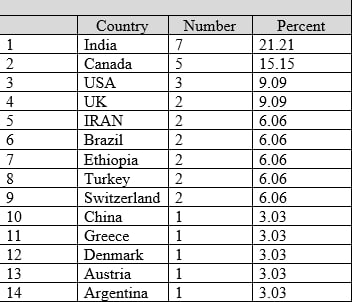

According to Table 3, the distribution of studies in different countries is also easily understood. About 14 countries have directly studied this phenomenon, and some countries have conducted joint studies.

Table No. 3- Frequency distribution of articles according to the place of research

1. Stigma in Family Members of Bipolar Patients: According to studies, the primary caregivers and other family members of bipolar patients also experience stigma. The public blames family members for incompetence on the patient, leading to the onset or recurrence of the disease. As a result, family members avoid attending social events and try to hide the affected member from society as much as possible. The study of Sharma et al. showed that the care burden for the families of bipolar patients is mainly felt in leisure time, during communication with others, as well as in financial issues, and there was no significant difference in the experience of stigma between families with different socio-economic conditions (Sharma et al., 2017). According to a study by Grover, the caregivers of bipolar patients experience considerable dependence and stigma. There is a positive and significant correlation between more stigma and lower-income, as well as less emotional support in these individuals (Grover et al., 2019). The results of Bassirnia showed that both bipolar patients and their treatment counterparts experience internal stigma, and there was a positive and significant relationship between internal stigma and introversion personality trait (Bassirnia et al., 2015). According to the study of Lepouriel, bipolar patients’ family members experienced stigma in five different dimensions, including language, identity, emotions, others’ reactions, and coping with bipolar disorder, highlighting the importance of specialized interventions to reduce stigma in bipolar patients’ families (Richard-Lepouriel et al., 2021).

2. Predictors of Stigma in Bipolar Patients and Their Families

The analysis of studies showed that several factors could pave the path for stigma in bipolar patients and their families. These factors are known as the predictors of stigma, which can either alone or in combination with each other create stigma. According to studies by Bonnington and Rose, social and cultural structures influence the atmosphere experienced by patients with bipolar disorder. These structures include stereotypes, norms, types of power distribution, communication methods, discriminative categories and labels, health care system, equality law, welfare system, and job status (Bonnington and Rose, 2014). The results of Shumet et al. showed that about 24.9% of patients with bipolar disorder had internal stigma based on the ISMI scale, which was significantly associated with unemployment, low education, low self-esteem, poor social support, and more than three times hospitalization (Shumet et al., 2021). According to the results of Thome, hospitalization disrupts the patient’s various aspects of life, leading to poor performance and consequently the experience of stigma. In the recent study, the presence of depression symptoms and the age of treatment onset and diagnosis were also associated with internal stigma (Thomé et al., 2012). According to Cerit et al., the three predictors of bipolar patients’ performance were depression severity, perceived social support, and internal labeling, respectively (Cerit et al., 2012). Based on a study by Sarisoy, internal stigma is seen in one in five bipolar patients, and anxiety or fear of communicating with others was more common in bipolar patients with internal stigma than in those without internal stigma (Sarısoy et al., 2013). The results of another study by Howland showed that internal stigma and self-efficacy were associated with each other, and internal stigma was also associated with depression symptoms such as anxiety, as well as feeling guilty and suspicious in patients with bipolar disorder (Howland et al., 2016). According to Nilsson’s study, the prevalence of stigma was between 37 and 57% in bipolar patients and their families. In addition, it was noted that stigma in bipolar patients was influenced by hospitalization in psychiatric hospitals and the ability to work, and psychosocial factors and emotional attitudes were reported as two

important factors in labeling (Ellison et al., 2015). Pal et al., in their study, reported that internal stigma in bipolar patients was significantly associated with factors such as monthly income, job and social performance, and education, and the fact that internal stigma significantly influenced the self-esteem, participation, and quality of life of bipolar patients (Pal, 2020). Another study by Clemente revealed that bipolar patients experience less stigma due to the individualistic culture in developed societies. This is while stronger interactions and cohesion between people in underdeveloped societies can essentially enhance stigma in these patients (Clemente et al., 2017). Engidaw described that tolerance to stigma was low in patients with bipolar disorder, which could be related to inadequate education and unemployment in these patients. Having academic education and a suitable job can boost self-esteem in these patients and their families, increasing their self-satisfaction and causing them to become less affected by others’ judgments and prejudices (Engidaw et al., 2020).

3. Consequences of Sigma in Bipolar Patients and Their Families Stigma has considerable consequences for bipolar patients and their families. As noted by Bhattacharyya, stigma causes bipolar patients to experience low self-esteem and a poor quality of life (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019). Pal’s study showed that in the manic phase, bipolar patients following perceived stigma start to expose their family members and their illness, leading to serious consequences for the patient and the family and bringing them social exclusion (Pal, 2020). According to a study by Noak, stigma significantly decreases the participation of bipolar patients in society, making it difficult for them to acquire credible information about the disease, even via online resources (Noack et al., 2016). Likewise, Kumar et al. noted that one of the most important consequences of stigma was disease relapse, facilitated by factors such as witnessing unfair behaviors by family members, the community, or the workplace (Kumar et al., 2020). The results of a study by Michalak showed that internal stigma could significantly affect self-management by bipolar patients. A reduction in self-management following internal stigma in these patients leads them to constantly regain their lost identities and roles in society (Michalak et al., 2011). As Sadighi noted, stigma in patients with bipolar disorder has remarkable effects on the quality of life of these patients and reduces their psychosocial performance and self-esteem (Sadighi et al., 2015). The study of Chi-Hung Au revealed that bipolar patients employ strategies such as avoiding others and social isolation to deal with stigma. Decreased self-esteem is the last phase in self-stigmatization and the most important phase in determining psychosocial performance (Au et al., 2019). According to another study by Vazquez, a high perceived stigma score was directly and significantly

correlated with a low-performance score (Vázquez et al., 2011). Karidi et al. showed in their study that stigma itself led to social deprivation and poor performance in individuals, and the fact that psychiatric disorders have a direct and profound effect on self-stigma (Karidi et al., 2015). Likewise, Post et al. described that quality of life was significantly associated with resilience, internal stigma, and residual symptoms in bipolar patients. The recent study results showed that even during recovery, bipolar patients experience a much poorer quality of life and lower resilience compared with healthy individuals (Post et al., 2018). Based on another report by Quenneville, an increasing score of internal stigma influences quality of life and job performance in bipolar patients (Quenneville et al., 2020). According to Grover’s study on bipolar patients, internal stigma was seen in 28%, the experience of discrimination in 38.9%, experienced stigma after hiding from others in 28.6%, and social isolation in 28.6% of the patients. Regarding participation, about two-fifths of the patients revealed minimal activities, and finally, high levels of stigma were directly related to reduced mean life expectancy (Grover et al., 2016). The results of a study by Brohan demonstrated that 21.7%, 59.7%, and 71.6% of bipolar patients experienced self-stigma, resistance to stigma, and discrimination, respectively (Brohan et al., 2011). Based on Mileva’s study, more than 50% of respondents believed that stigma had

affected their life quality and reduced their self-esteem (Mileva et al., 2013).

4- Effective Interventions and Strategies to Reduce Stigma in Bipolar Patients and Their Families Numerous strategies and interventions have been suggested to cope with stigma and reduce its consequences in bipolar patients and their family members. Some of these strategies have been studied, and their positive outcomes in reducing stigma have been somehow illuminated. In the study of Michalak, integrated KT methods were employed in the form of designing and performing theater to improve stigmatizing attitudes. The results showed that caregivers, bipolar patients, and their families experienced significant improvements in their labeling attitudes immediately after performing the program (Michalak et al., 2014). In another study by Keshavarzpir, psychological education, as one of the supportive approaches to alleviate psychiatric problems, was reported to improve patients’ understanding of psychiatric disorders, which can positively affect self-esteem and the ability to manage stigma (Keshavarzpir et al., 2020). The results of a study by Richardson showed that cognitive-behavioral-based psychological education increased perceived improvement in bipolar patients and delayed the recurrence of mood disorders, highlighting the importance of factors such as identity, hope, optimism regarding the future, and

empowerment. Overall, the intervention employed in the recent study was shown to reduce stigma and improve the quality of life in bipolar patients (Richardson and White, 2019). Hawke et al. used a movie-based intervention and noted its significant impacts on reducing stigma in caregivers. Students also showed remarkable improvements in their tendency not to reduce the social distance from bipolar patients; which was also remarkable in the general public (Hawke et al., 2014). Studies have also pointed out the positive effects of non-pharmaceutical therapies on reducing stigma in bipolar patients, and it has been suggested to use these methods, as well as psychotherapy, in addition to pharmaceutical therapy to reduce stigma and increase resilience to stigma and quality of life in these patients (Post et al., 2018). As stated by Mileva, to find effective strategies to cope with stigma in bipolar patients and their families, we must first know how they experience the phenomenon, and ISE is a valuable and reliable tool allowing us to reach this goal with high certainty in different cultures (Mileva et al., 2013).

Discussion This study aimed to investigate the predictors, consequences, and coping strategies of stigma in bipolar patients and their families. Our findings suggest that in addition to bipolar patients, their families also experience different levels of stigma, whose consequences, in general, include feelings of

disrespect, disregard, and discrimination in society. To cope with this phenomenon, families often choose social isolation and withdrawal. They deprive themselves and the patient of receiving treatment by hiding the ill family member and delaying seeking treatment. Social stigma is the most devastating when the family accepts it and internalizes the negative views of the community, a phenomenon called internalized or emotional stigma. This is consistent with the findings of Bruni (Bruni et al., 2018), Sharma (Sharma et al., 2017), Wong (Wong et al., 2009), Bassirnia (Bassirnia et al., 2015), Park (Park and Park, 2014), Grover (Grover et al., 2019), Ando (Ando et al., 2013), and Leporil (Richard-Lepouriel et al., 2021). The analysis of available studies revealed that many factors could effectively predict stigma in bipolar patients and their families, including social and cultural structures, inefficient welfare system, low education, unemployment or lack of a suitable job, low self-esteem, poor communication skills, lack of intimate relationships with others, lack of being understood by others, poor social support, collectivist cultures, young age at disease onset, recurrent hospitalizations, gender, disease severity, disease duration, and discriminative labels. This finding was consistent with the results of Bonnington (Bonnington and Rose, 2014), Clemente (Clemente et al., 2017), Engidaw (Engidaw et al., 2020), Shumet (Shumet et al., 2021), Thome (Thomé et al., 2012), Cerit (Cerit et al., 2012),

Sarisoy (Sarısoy et al., 2013), Howland (Howland et al., 2016), Ellison (Ellison et al., 2015), Nilsson (Nilsson et al., 2016), and Pal (Pal, 2020).

Stigma causes bipolar patients and their families to suffer from severe psychological distress in addition to the pain and agony inflicted by the disease. Studies have pointed out several consequences of stigma in these individuals, such as reduced participation, social deprivation, social exclusion, social isolation, restriction in social functions such as job performance and education, low self-esteem, poor quality of life, the prolongation of the treatment course, disease recurrence, hiding the disease, experiencing discrimination and injustice, and finally reduced life expectancy and resilience. These results were in line with the studies of Bhatacharyya (Bhattacharyya et al., 2019), Pal (Pal, 2020), Noak (Noack et al., 2016), Kumar (Kumar et al., 2020), Michalak (39), Sadighi (Sadighi et al., 2015), Au (Au et al., 2019), Vazquez (Vázquez et al., 2011), Karidi (Karidi et al., 2015), Post (Post et al., 2018), Quenneville (Quenneville et al., 2020), Grover (Grover et al., 2016), Brohan (Brohan et al., 2011), and Mileva (Mileva et al., 2013). Several interventions have been suggested to alleviate stigma and its consequences in bipolar patients and their family members. The positive outcomes of these interventions included boosting public awareness and amending public attitudes toward bipolar disorder, using alternative non-

pharmaceutical therapies, enhancing self-esteem, using the ISE tool to identify patients’ experiences, psychological education, and cognitive-behavioral interventions aiming to increase patients’ perceived recovery and sense of disease control. These results were in parallel with those of Michalak (Michalak et al., 2011), Keshavarzpir (Keshavarzpir et al., 2020), Richardson (Richardson and White, 2019), Mileva (Mileva et al., 2013), Post (Post et al., 2018), and Hawke (Hawke et al., 2014).

The limitations of this study are the possibility of not including in-press articles, exclusion of non-English articles, the lack of possibility for searching in a number of other databases, and the possibility of the non-retrieval of all related studies using the combinations of the utilized keywords. So, to acquire all related articles, in addition to searching using a combination of syntax, authors also searched a considerable number of retrieved articles manually.

Conclusion The results showed that stigma hurdles the treatment of bipolar disorder due to labeling, followed by hiding the disorder by families and their delay in seeking treatment. Misconceptions such as considering these patients dangerous and unpredictable and regarding families as culprits and irresponsible are present in society and at the workplace, educational settings, the health care system, the judiciary system, and even in the family.

Therefore, it is necessary to take necessary measures to normalize bipolar disorder at the community level so that the general public becomes aware of its nature and understands stigma towards patients with mental disorders. The findings of this study can provide useful information about stigma in patients with bipolar disorder, which can be used for mental health policymaking at the macro level, as well as by health care providers, the general public, and families at the micro level.

Declaration

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. The present study is part of a Ph.D. dissertation (ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.249) in social work approved by the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who participated in this study. We would also like to appreciate the full cooperation of the university officials at the staff of Razi Psychiatric Hospital.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Authors’ information

Not applicable

References

AGGARWAL, N. K., BALAJI, M., KUMAR, S., MOHANRAJ, R., RAHMAN, A., VERDELI, H., ARAYA, R., JORDANS, M., CHOWDHARY, N. & PATEL, V. 2014. Using consumer perspectives to inform the cultural adaptation of psychological treatments for depression: a mixed methods study from South Asia. Journal of affective disorders, 163, 88-101.

ANDO, S., KASAI, K., MATAMURA, M., HASEGAWA, Y., HIRAKAWA, H. & ASUKAI, N. 2013. Psychosocial factors associated with suicidal ideation in clinical patients with depression. Journal of affective disorders, 151, 561-565.

ANGST, J. 2013. Bipolar disorders in DSM-5: strengths, problems and perspectives. International journal of bipolar disorders, 1, 1-3.

AU, C.-H., WONG, C. S.-M., LAW, C.-W., WONG, M.-C. & CHUNG, K.-F. 2019. Self-stigma, stigma coping and functioning in remitted bipolar disorder. General Hospital Psychiatry, 57, 7-12.

BASSIRNIA, A., BRIGGS, J., KOPEYKINA, I., MEDNICK, A., YASEEN, Z. & GALYNKER, I. 2015. Relationship between personality traits and perceived internalized stigma in bipolar patients and their treatment partners. Psychiatry research, 230, 436-440.

BHATTACHARYYA, D., YADAV, A. & DWIVEDI, A. K. 2019. Relationship between stigma, self-esteem, and quality of life in euthymic patients of bipolar disorder: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Marine Medical Society, 21, 145.

BİLİR, M. K. 2018. Deinstitutionalization in Mental Health Policy: from Institutional-Based to Community-Based Mental Healthcare Services. Hacettepe Sağlık İdaresi Dergisi, 21, 563-576.

BONNINGTON, O. & ROSE, D. 2014. Exploring stigmatisation among people diagnosed with either bipolar disorder or borderline personality disorder: A critical realist analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 7-17.

BROHAN, E., GAUCI, D., SARTORIUS, N., THORNICROFT, G. & GROUP, G. E. S. 2011. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with bipolar disorder or depression in 13 European countries: The GAMIAN–Europe study. Journal of affective disorders, 129, 56-63.

BRUNI, A., CARBONE, E. A., PUGLIESE, V., ALOI, M., CALABRÒ, G., CERMINARA, G., SEGURA-GARCÍA, C. & DE FAZIO, P. 2018. Childhood adversities are different in schizophrenic spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. BMC psychiatry, 18, 391.

CERIT, C., FILIZER, A., TURAL, Ü. & TUFAN, A. E. 2012. Stigma: a core factor on predicting functionality in bipolar disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 484-489.

CLEMENTE, A. S., SANTOS, W. J. D., NICOLATO, R. & FIRMO, J. O. A. 2017. Stigma related to bipolar disorder in the perception of psychiatrists from Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil. Cadernos de saude publica, 33, e00050016.

CONNELL, J., O’CATHAIN, A. & BRAZIER, J. 2014. Measuring quality of life in mental health: are we asking the right questions? Social science & medicine, 120, 12-20.

ELLISON, N., MASON, O. & SCIOR, K. 2015. Public beliefs about and attitudes towards bipolar disorder: Testing theory based models of stigma. Journal of affective disorders, 175, 116-123.

ENGIDAW, N. A., ASEFA, E. Y., BELAYNEH, Z. & WUBETU, A. D. 2020. Stigma Resistance and Its Associated Factors among People with Bipolar Disorder at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Depression Research and Treatment, 2020.

GOFFMAN, E. 2003. Stigma. Praha: Sociologické nakladatelství (SLON).

GROVER, S., ANEJA, J., HAZARI, N., CHAKRABARTI, S. & AVASTHI, A. 2019. Stigma and its correlates among caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 41, 455-461.

GROVER, S., HAZARI, N., ANEJA, J., CHAKRABARTI, S. & AVASTHI, A. 2016. Stigma and its correlates among patients with bipolar disorder: A study from a tertiary care hospital of North India. Psychiatry Research, 244, 109-116.

GUR, K., SENER, N., KUCUK, L., CETINDAG, Z. & BASAR, M. 2012. The beliefs of teachers toward mental illness. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 47, 1146-1152.

HAWKE, L. D., MICHALAK, E. E., MAXWELL, V. & PARIKH, S. V. 2014. Reducing stigma toward people with bipolar disorder: impact of a filmed theatrical intervention based on a personal narrative. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60, 741-750.

HENDERSON, C., EVANS-LACKO, S. & THORNICROFT, G. 2013. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. American journal of public health, 103, 777-780.

HOWLAND, M., LEVIN, J., BLIXEN, C., TATSUOKA, C. & SAJATOVIC, M. 2016. Mixed-methods analysis of internalized stigma correlates in poorly adherent individuals with bipolar disorder. Comprehensive psychiatry, 70, 174-180.

JOLFAEI, A. G., ATAEI, S., GHAYOOMI, R. & SHABANI, A. 2019. High Frequency of Bipolar Disorder Comorbidity in Medical Inpatients. Iranian journal of psychiatry, 14, 60.

KALTENBOECK, A., WINKLER, D. & KASPER, S. 2016. Bipolar and related disorders in DSM-5 and ICD-10. CNS spectrums, 21, 318-323.

KARIDI, M., VASSILOPOULOU, D., SAVVIDOU, E., VITORATOU, S., MAILLIS, A., RABAVILAS, A. & STEFANIS, C. 2015. Bipolar disorder and self-stigma: A comparison with schizophrenia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 209-215.

KESHAVARZ, FATEMI, MARDANI, ESMAIELY & HAGHANI 2018. Effect of psychoeducation program on internalized stigma of clients with bipolar disorder.

KESHAVARZPIR, Z., SEYEDFATEMI, N., MARDANI-HAMOOLEH, M., ESMAEELI, N. & BOYD, J. E. 2020. The Effect of Psychoeducation on Internalized Stigma of the Hospitalized Patients with Bipolar Disorder: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 42, 79-86.

KNIGHT, M. T., WYKES, T. & HAYWARD, P. 2006. Group treatment of perceived stigma and self-esteem in schizophrenia: a waiting list trial of efficacy. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 34, 305-318.

KOSCHORKE, M., PADMAVATI, R., KUMAR, S., COHEN, A., WEISS, H. A., CHATTERJEE, S., PEREIRA, J., NAIK, S., JOHN, S. & DABHOLKAR, H. 2014. Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Social Science & Medicine, 123, 149-159.

KUMAR, K. S., VANKAR, G. K., GOYAL, A. D. & SHARMA, A. S. 2020. Stigma and discrimination in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar mood disorder. Annals of Indian Psychiatry, 4, 33.

MCCANN, T. V., LUBMAN, D. I. & CLARK, E. 2011. Responding to stigma: first-time caregivers of young people with first-episode psychosis. Psychiatric Services, 62, 548-550.

MICHALAK, E., LIVINGSTON, J. D., HOLE, R., SUTO, M., HALE, S. & HADDOCK, C. 2011. ‘It’s something that I manage but it is not who I am’: reflections on internalized stigma in individuals with bipolar disorder. Chronic Illness, 7, 209-224.

MICHALAK, E. E., LIVINGSTON, J. D., MAXWELL, V., HOLE, R., HAWKE, L. D. & PARIKH, S. V. 2014. Using theatre to address mental illness stigma: a knowledge translation study in bipolar disorder. International journal of bipolar disorders, 2, 1-12.

MILEVA, V. R., VÁZQUEZ, G. H. & MILEV, R. 2013. Effects, experiences, and impact of stigma on patients with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 31.

NILSSON, K. K., KUGATHASAN, P. & STRAARUP, K. N. 2016. Characteristics, correlates and outcomes of perceived stigmatization in bipolar disorder patients. Journal of affective disorders, 194, 196-201.

NOACK, K., ELLIOTT, N. B., CANAS, E., LANE, K., PAQUETTE, A., LAVIGNE, J.-M. & MICHALAK, E. E. 2016. Credible, centralized, safe, and stigma–free: What youth with bipolar disorder want when seeking health information online. UBC Medical Journal, 8.

PAL, A. 2020. A cross-sectional study of internalized stigma in euthymic patients of bipolar disorder across its predominant polarity. Indian Journal of Social Psychiatry, 36, 73.

PARK, S. & PARK, K. S. 2014. Family stigma: A concept analysis. Asian Nursing Research, 8, 165-171.

POST, F., PARDELLER, S., FRAJO-APOR, B., KEMMLER, G., SONDERMANN, C., HAUSMANN, A., FLEISCHHACKER, W. W., MIZUNO, Y., UCHIDA, H. & HOFER, A. 2018. Quality of life in stabilized outpatients with bipolar I disorder: Associations with resilience, internalized stigma, and residual symptoms. Journal of affective disorders, 238, 399-404.

QUENNEVILLE, A. F., BADOUD, D., NICASTRO, R., JERMANN, F., FAVRE, S., KUNG, A.-L., EULER, S., PERROUD, N. & RICHARD-LEPOURIEL, H. 2020. Internalized stigmatization in borderline personality disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in comparison to bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders, 262, 317-322.

RICHARD-LEPOURIEL, H., AUBRY, J.-M. & FAVRE, S. 2021. Is Coping with Stigma by Association Role-Specific for Different Family Members? A Qualitative Study with Bipolar Disorder Patients’ Relatives. Community Mental Health Journal, 1-14.

RICHARDSON, T. & WHITE, L. 2019. The impact of a CBT-based bipolar disorder psychoeducation group on views about diagnosis, perceived recovery, self-esteem and stigma. the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 12.

SADIGHI, G., KHODAEI, M. R., FADAIE, F., MIRABZADEH, A. & SADIGHI, A. 2015. Self stigma among people with bipolar-I disorder in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal, 13, 32-28.

SARıSOY, G., KAÇAR, Ö. F., PAZVANTOĞLU, O., KORKMAZ, I. Z., ÖZTÜRK, A., AKKAYA, D., YıLMAZ, S., BÖKE, Ö. & SAHIN, A. R. 2013. Internalized stigma and intimate relations in bipolar and schizophrenic patients: a comparative study. Comprehensive psychiatry, 54, 665-672.

SHAMSAIEE, KERMANSHAHI & VANA 2013. The meaning of health from the perspective of a family member caring for a patient with bipolar disorder: A qualitative study. Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, 22, 52-65.

SHARMA, H., SHARMA, B. & SHARMA, D. B. 2017. Burden, perceived stigma and coping style of caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Int J Health Sci Res, 7, 84-94.

SHUMET, S., ANGAW, D., ERGETE, T. & ALEMNEW, N. 2021. Magnitude of internalised stigma and associated factors among people with bipolar disorder at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 11, e044824.

SIBITZ, I., UNGER, A., WOPPMANN, A., ZIDEK, T. & AMERING, M. 2011. Stigma resistance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin, 37, 316-323.

THOMÉ, E., DARGÉL, A., MIGLIAVACCA, F., POTTER, W., JAPPUR, D., KAPCZINSKI, F. & CERESÉR, K. 2012. Stigma experiences in bipolar patients: the impact upon functioning. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19, 665-671.

VÁZQUEZ, G., KAPCZINSKI, F., MAGALHAES, P., CÓRDOBA, R., JARAMILLO, C. L., ROSA, A., DE CARMONA, M. S., TOHEN, M. & ON BIPOLAR, T. I.-A. N. 2011. Stigma and functioning in patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of affective Disorders, 130, 323-327.

WONG, C., DAVIDSON, L., ANGLIN, D., LINK, B., GERSON, R., MALASPINA, D., MCGLASHAN, T. & CORCORAN, C. 2009. Stigma in families of individuals in early stages of psychotic illness: family stigma and early psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 3, 108-115.

Table 1 – Information of articles that met the inclusion criteria.

Table No. 2 – Frequency distribution of articles by research method

Table No. 3- Frequency distribution of articles according to the place of research

Figure 1. The process of the inclusion and exclusion of articles in the present research